Fighting the Growing Global Wildfire Crisis

“Where we had beautiful trees, it’s now black”. These are the words of Amber Yoney and her mother Susan Miller, who filmed their terrifying escape from the Camp Fire in Butte County, California. In 2018, the Camp Fire burned a total of 153,336 acres, and destroyed 18,804 structures, ultimately causing 85 civilian fatalities. Unfortunately, landscape fires like the Camp Fire are becoming frighteningly common around the globe.

A new report from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) warns that fires of this magnitude and greater may increase globally by 14% by the end of the decade and 50% by 2100 if no preventative measures are taken. Even places where these fires are extremely rare like the Arctic are not immune. This article will examine some of the causes of this phenomenon, and take a look at how ESG-minded entities are responding and fighting the growing global wildfire crisis.

Causes and Effects of Wildfires

Global Tinderbox With rising temperatures around the globe, fuel for landscape wildfires is becoming more abundant. While around 80% of global wildfires crisis occur in grasslands each year, abnormal heat is expanding the arena into forestland. Abnormal heat can kill trees, and dry out dead grass on the forest floor.

In the past, wildfires would remain close to the ground, as the flames were repelled by the moisture in the trees. However, where fires are able to literally climb dead trees, the wildfires become extreme and often out of control. Further, drought can also increase the probability of spontaneous ignition and the rate at which fire spreads. Low precipitation and extreme heat also create a negative cycle leading to decreased streamflow, dry soils, and large-scale tree deaths. When the next fire season comes around, dryer and more barren environments only worsen the situation.

Longer Fire Seasons

Summer wildfire seasons are already 40 to 80 days longer on average than they were 30 years ago. This increased season length has also lengthened, with one study measuring the growth across 29.6 million square km (25.3%) of the Earth’s vegetated surface, leading to an increase in global mean fire weather season length by 18.7%. Following the cyclical patterns seen in droughts, hotter, longer fire seasons also increase the probability of extreme weather events like tornados, severe lightning storms, and extreme winds, exasperating droughts and increasing the probability of out-of-control wildfires over again.

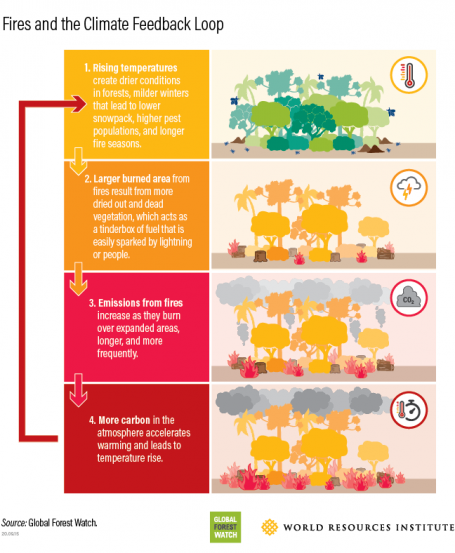

Atmospheric Carbon

Global fires have notable impacts on the global carbon cycle. Current estimates measure the immediate direct carbon emissions from these fires at about 2 gigatons (G1) annually into the atmosphere.

This production in turn affects carbon sinks like the oceans and forests, which are struggling to contain and process the increasing volumes. In fact, about 20% of the global fire emissions represent a source of carbon that could be deemed “irreversible” on decadal to centennial time scales, since it cannot be stored by vegetation regrowth or soil carbon rebuild.

This is particularly prevalent in peatland fires and tropical deforestation which over time have cascading effects on enhanced tree mortality – ultimately leading to more carbon losses. Deforestation of carbon sinks also negatively affects companies’ ability to reliably invest in or trade carbon credits. Often these carbon credits are measured by these carbon sinks’ ability to take in and hold carbon over long periods of time. However, with such an unpredictable variable as wildfires introduced, it is critical to monitor and protect these ecosystems to accurately rely on the carbon credit system.

Solutions and Initiatives Addressing the Challenge

Fight Fire with Fire

As Matthew Graeve of The Nature Conservancy states, “It is imperative that we acknowledge and restore fire as a necessary part of natural systems.” Smaller scale, controlled and prescribed burns can both reduce the extremity of wildfires and increase the overall health of local biomes.

Fires can eliminate dead organic material which impedes organisms’ ability to access nutrients in the soil. In so doing, nutrients released from the burned material return more efficiently into the soil than long-term decay, increasing overall soil fertility. The antithesis of the negative drought feedback loop, prescribed fires create a positive feedback loop whereby over years of practicing controlled burns, a biome’s resiliency to fire builds dramatically.

Businesses and Governments Taking Initiative

Small and large businesses alike have taken on the challenge presented by global wildfire crisis. For example, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Zack Parisa (co-founder of SilvaTerra) created a startup whose software creates forest maps that detail the average ages and categories of trees across acres of land. This helps agencies target which vegetation should be removed to prevent damaging forest fires.

Other technologies have also developed, including A.I enabled fire detection, fire risk analysis systems, and more. Startups and companies running these tools have expressed the challenges of receiving government funding, so investors have a uniquely important role in the future of these ventures. Investing in these technologies not only addresses the immediate emergencies posed by wildfires but builds resilience over time which protects both environmental and economic stability.

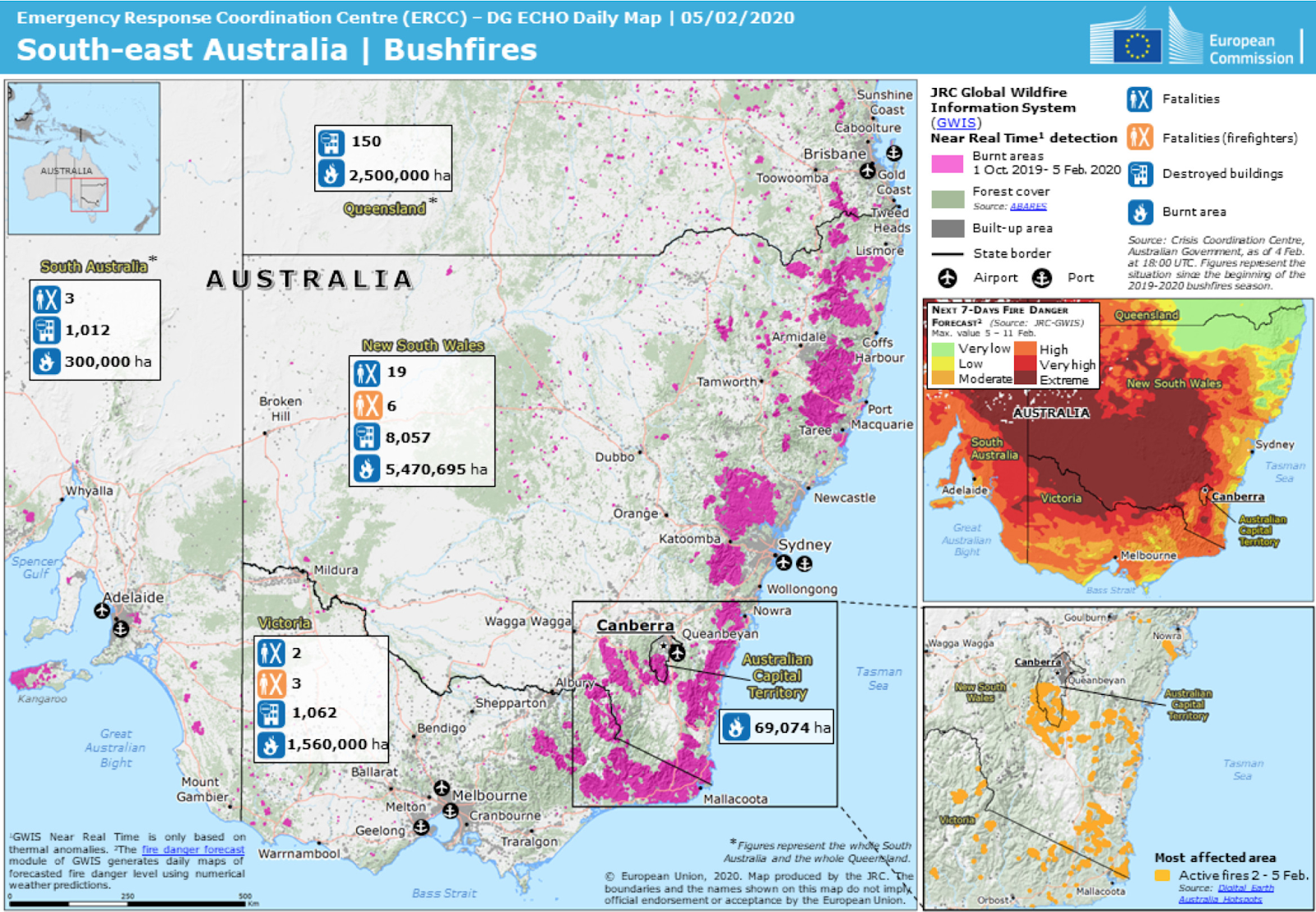

Monitoring is a critical component of attacking the global wildfire crisis. Initiatives like the Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS) is taking on the task, and providing invaluable information on both immediate issues and long-term data. GWIS is a joint initiative of the Group on Earth Observations (GEO), the NASA Applied Research, and the EU Copernicus work programs. It has been tracking the spread of global wildfires since 2001, analyzing the impact of fire emissions, damage to infrastructure, and the ultimate environmental impact. It also places special focus on assisting developing countries whose access to such detailed information is limited by lack of resources or funding.

For example, GWIS played an important role throughout and after Australia’s 2019-2020 bushfire season. As noted by Earth Observations, during that period Australia did not possess a unified fire information system on a national scale. This tool filled that gap, not only allowing Australia to respond efficiently but also giving assisting organizations like the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) the tools to spread the word to support agencies across the globe. Building these monitoring systems is important for both proactive and reactive responses to wildfires.

Conclusion

Extreme global wildfires crisis pose a considerable threat to local and global economies and environments. However, investing in those businesses and communities that are addressing the crisis is necessary, possible, and has the potential to make a positive change in the trajectory of climate change.

Leave a Reply